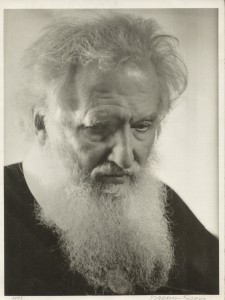

Рома М. Гайда

У цьому році обходимо дві дати, які особливо пов’язані з нинішним святом 80-ліття професора Рудницького: святом родинним і святом громадським, а для мене також трохи персональним. Родина напевно скаже від себе про свого улюбленого дідуся і батька, ну й про сприятливу бабусю і матір, значить про особливих батьків — подружжя Леоніда та Ірени. Сам громадський аспект Леоніда можна розділити на наукову, академічну та церковно-релігійну сторінки. Я зупинюся на останнім, a саме на мирянському русі натхненим Ісповідником віри Йосифом Сліпим. Якраз у цьому році сповняється 50-ліття Патріярхального Товариства з яким тісно пов’язане життя нашого солізіянта.

Патріярхальний рух передовсім відповів на виклик часу. Його конкретний вимір є в самій основі повноти кожної Східної Церкви на підставі древньої традиції апостольських Церков Сходу і Заходу — самобутність її духовості та самобутність правління. Переорієнтація від тодішних прийнятих норм догідництва ватиканським чиновникам до розуміння цілісности Церкви Києво-Візантійської традиції було великим осягненням завдяки надзвичайному главі Церкви Йосифові Сліпому і його різним послідовникам. Згадаймо лише професорів Василя Маркуся, Богдана Лончину, Мирослава Лабуньку; редакторів Романа Данилевича, Василя Качмара; інжинера Сидора Тимяка; скрипаля Дарію Кузик, журналістку Еву Піддубчишин… Їх характеризує поєднання віри і науки, відданість родині, успіх професійний, та рівночасно у вирішальний період увага їхньої громадської діяльності для уніфікації – розсіяної по світі та поневоленої у Совєтському Союзі – Української Греко-Католицької Церкви. Владика Борис Ґудзяк називає працю Патріярхального Товариства реформаторським рухом.

Відданість Леоніда Рудницького ідеям Патріярха Йосифа виринули з духовних заложень віруючої людини, яка є в постійному пошуці відповідей на життєві питання. Віра є актом розуму і волі. В контексті американської культури віра є індивідуальна і приватна справа. Крапка. І навіть в сучасному думанні її відокремлюють від так званої (і в лапках) «організованої релігії», що є віроісповідання спільноти історичної Церкви.

Один із добре знайомих професора Рудницького, історик християнства і християнського богослов’я та інтелектуальної історії середньовіччя, Ярослав Пелікан, має цікаві спостереження. Визнаючи, що віра є індивідуальна і суб’єктивна, в неї притаманні висоти і низи, але ніхто не може числити постійно перебувати в стані духовного піднесеня. Вірі потрібна безпереривність з місяця на місяць, з року в рік. Та й це не все. На думку Пелікана необхідно мати пов’язання із спільнотою віруючих та тяглість минулих віків. Коливання, які нераз приходять, можуть легко звести на манівці. Захищення віруючої спільноти є Церква. Далі Пелікан доводить до сповідування самого креда – «Вірую» (як у «Вірую в єдиного Бога Отця… »), що ми мовимо кожного дня і на кожній Божественній літургії, в якій заявляємо загальні принципи і переконання, і святкуємо їх. В ній зберігається віра, яка відтак підтверджується віруючою людиною. Причина, для чого я наводжу ці думки Пелікана, є для того, що у нашого солізіянта ці речі природно пов’язані. Віра, віроісповідання, церковна спільнота із єрархічною структурою і тяглістю від далекої давнини.

Для повоєнної еміграції не можна применшити значення появи на волі ісповідника віри Йосифа, при чому церковний провід не зміг його відповідно представити нащадкам раніших еміграцій. По-перше, в контексті власного пережиття большевицького терору та насильницької ліквідації Греко-Католицької Церкви в Україні, визволення її митрополита Йосифа Сліпого було чудо майже на рівні воскресіння. По друге, невимовно смілива ідея патріярхату стрясла суспільство. Неочікувана і далекосяжна пропозиція породила різну реакцію – за і проти з різних кутків своїх і чужих.

Кухонна політика домашніх політикантів була в силі її знівечити приміром такими заявами, що у Йосифа Сліпого сполосканий мозок якого совєтський режим навмисно вислав для нашого знищення. А знов з церковної сторони не помагали мильно вплутані чеснота покори і вимоги підпорядкування церковним властям. Зчинився поважний виклик який вимагав застановлення над елементарними питаннями із знання релігії, знання історії Церков Сходу і Заходу, з еклезіології (що є богослов’я правління Церкви у виконуванні її місії), Берестейська Унія і помісність, церковне право і т.п. Будь-яка людина з почуттям відповідальности мусіла застановитися як розібратися у цьому безпорядку щоби дійти до совісних висновків. Люди уцерковлені і з високою освітою часто мусіли вийти поза рамці своїх знань щоби попровадити церковне питання у змислі церковного буття, бо таки треба знати що це таке «еклезіологія», у чому різниться його розуміння перед і після Другого Ватиканського Собору, що воно пропонує нашій Церкві і т.п.. З одної сторони не був це легкий час для духовенства і мирян, а з другої — розв’язка дилеми відкрила унікальну нагоду розвинути внутрішний діялог до необхідних питань великого визову Патріярха Йосифа Сліпого. Іншими словами катеґоричне «carpe diem»!

Внутрішній діалог був інтенсивний і набрав різні форми. Конференції і симпозії поглиблювали і поширювали знання різних церковних ділянок – історії нашої Церкви, східного богослов’я, канонічного права та інші. В їх наслідок видавнича діяльність розповсюджувала усучаснене знання. З’їзди і конґреси мирян об’єднювали рух. Пресові конференції інформували світ. Виклади літними семестрами в унівеситеті св. Климентія Папи в Римі приготовляли молодші покоління для служіння Церкві і суспільству. Професор Рудницький у переважаючій більшості виконував у них якусь добру часть. У його бачені різних складових великої цілі не обмежувалися до ініціятив уже вичислених активностей. Починаючи від 1985 року через шість років він провадив радіопрограму спрямовану в Радянську Україну «Голос української діяспори». В ювілейному році тисячоліття хрещення Русі України Рудницький разом із покійним Лабунькою подбали про вшанування докторатом honoris causa Патріярха Мирослава Івана Любачівського в університеті Ля Саль. Гоноровий докторат на вигляд може дрібничкова справа, але гідність особи і Церкви у змаганні за визнання ще раз виявила перед світом наше рішуче стремління. Можна сказати, що такі старання і добра доповідь у природі академіка, то таки відповідати за пресову конференцію з міжнародною пресою у Римі не цілком те саме, що виклади з університетської катедри. Контакти з аґенціями, папки матеріялу, збір співбесідників з пресою, вирішення пріоритетів в передачі інформації тощо. Звичайно, добре зроблена робота завжди виглядає легкою.

В результаті інтелектуальної праці довкруги питання самоуправління Греко-Католицької Церкви були й неукраїнські науковці, як професори о. Джордж Малоні і Томас Бирд, автор о. Алексіс Флоріді, вже згадуваний Ярослав Пелікан та інші. Пелікана приєднав Леонід Рудницький і переконав його написати книжку про Патріярха Йосифа, яка цього року, знову завдяки заходам Рудницького, вийшла в українському перекладі під заголовком «Ісповідник між Сходом і Заходом: портрет українського кардинала Йосифа Сліпого».

Головним осягненням патріярхального руху було прийняття ідеї патріярхату, що до часу незалежности України взяло трохи більше одного покоління. Що за часто буває в українському середовищі, це поверховне спринимання і знання подвижників великих ідей. Велика людина відходить і ми забуваємо основи її праці для продовження в нових обставинах. Тяглість розвитку потребує інтелектуального зацікавлення. І саме у цьому професор Рудницький досі заповнює поважну прогалину.

У 120 річницю з дня народження Йосифа Сліпого, а 28 років від його смерти, в лютому 2012 року відбулася дводенна міжнародна наукова конференція. В університеті Ля Саль спеціялісти представили богословські, еклезіяльні та екуменічні аспекти праці Патріярха. Серед п’ятьох науковців були два неукраїнці. Професор католицького університету Тільбурґу в Голяндії і секретар товариства католицьких богословів Европи, був Карім Шелькенс (Karim Schelkеns). У самому заголовку «З одного вигнання в інше: митрополит Йосиф Сліпий на II Ватиканському соборі» він схопив долю Ісповідника віри у вимірах напруження, що зігравалися за стінами Ватикану. Вільям Тайґ (William J. Tighe), знавець історії ренесансу і реформації та дописувач до поважного журналу релігійної тематики First Things порівняв паралелі між Йосифом Сліпим і Папою Бенедиктом ХУІ у їх увазі літургійним перекладам. Три українські доповідачі кинули світло на інші сторінки Блаженнішого. Бібліознавець о. Андрій Онуферко з Інституту ім. Митрополита Андрея Шептицького для Східньо-Християнських Студій в Оттаві, пояснив посилання у Святе Письмо і біблійну мову Старого Завіту у Заповіті Патріярха Йосифа. Він переконливо пов’язав глибину мисленя Йосифа Сліпого і траєкції нашої Церкви в майбутні покоління. Не меншого значення був історичний контекст Церкви поселенців у США від 1867 року до другої половини 20 століття щоби зрозуміти тяглість процесів у встановленні юрисдикції Києво-галицьких митрополитів поза межами України. У тому розумінні були доцільні три апостольські візитації нашої Церкви в Америці її духовним батьком, сказав спеціяліст історії Греко-католицької Церкви в США о. Іван Кащак. Про «Дух екуменізму в житті і праці Йосифа Сліпого» о. Іван Дацько представив намагання Йосифа Сліпого розуміти суть богословських коренів Сходу і Заходу та завдання єдности Церков. Професор УКУ та директор Інституту св. Клементія в Римі о. Дацько звернув увагу його послідовності. Патріярх Йосиф був переконаний про необхідність нашої Церкви працювати в дусі екуменізму з солідною основою духовної формації та академічних студій. Це був перший день.[1] В приміщені собору митрополії другий день конференції зосередився на людськості особи. Спогади колишніхсемінаристів доповнили інтелектуально богословський вимір теплотою гумору Блаженнішого, зацікавленням їх особистим життям та присутністю у їхніх буднях.

Наведення змісту конференції у 120 річницю народження Патріярха Йосифа зорганізованої нашим солізіянтом Леонідом Рудницьким є виразом поєднання науки і віри в подальшій праці започаткованій десятки років тому. Леоніда тривале зацікавлення засвідчує вплив Патріярха Йосифа, який оновлюється у продовженні ідеї патріярхату Йосифа Сліпого у доростанні духовної, богословської та еклезіяльної повноти, що були справжні напрямні Ісповідника віри.

Відомо, що патріярхальний рух змінився. Від боротьби за патріярхат перейшли на зміст патріяршої Церкви, бо жадна зверхня структура без наповнення змістом не вдержиться. Добрий приклад цього є Україна вкінці 2013 року. Значить, подбати щоби якнайширший загал був свідомий головних об’єднюючих критерій патріярхату, а саме Києво-візантійська духовість, богослов’я, літургічно-молитовне життя і богослов’я правління – що є еклезіологія, яка включає сопричастя Церков. На відміну сконцентрованого централізму за часів Патріярха Йосифа і після, Святіший Отець Франциск хилиться до децентралізації для кращого служіння Церкви у світі. Ось знову нагода подбати і припильнувати наше доростання щоби запевнити єдність Церкви на поселенях із Київським престолом визнаним патріярхатом. Між складовими цього проєкту є праця нашого солізіянта, видання двомісячника “ПАТРІЯРХАТ”, який доступною мовою доносить свідомість про ті питання своїм читачам, а в особливій катеґорії є Інститут ім. Митрополита Андрея Шептицького для Східньо-Християнських Студій, який реально і конкретно вставляє Києво-візантійську традицію в контексті потреб діяспори для кращого сповнення місії нашої Церкви на поселенях. Цей надзвичайний ресурс є також спадщиною Слуги Божого Йосифа Сліпого.

“Віра без діл мертва”, пише св. Апостол Яків (послання Якова 2:17). Роки праці професора Рудницького випливають із глибини душі. Ось так пише Леонід Рудницький в статті “Трохи зі серця, трохи з розуму” в січневому номері Патріярхат 2013 року:

“Вплив Патріярха Йосифа на людей моєї ґенерації був величезний. У ті не геройські, угодницькі часи Ostpolitic Ватикану ми, члени УГКЦ об’єднані в Патріярхальному русі [. . .] завдяки нашому Патріярхові відчули себе могутньої духовної спільноти…

“Я завжди буду вдячний Божому провидінню за те, що мав нагоду жити, коли Патріярха Йосиф був фізично між нас, і за те, що мав нагоду служити йому. Я завдячую тій людині дуже багато і як людина, і як науковець.”

За мого головства Патріярхального Товариства я завжди могла числити на добру пораду і співпрацю. Разом із теперішним головою Патріярхального Товариства д-ром Андрієм Сороковським і редактором журналу “Патріярхат” Анатолієм Бабинським висловлюємо признання і вдячність. Так, Слуга Божий Йосиф Сліпий дійсно бачив нас, нашу Церкву, активним чинником у встановлені і визнання патріярхату та суттєвого розуміння сопричастя з Намісником Св. Петра. Запрошуємо усіх присутніх з’єднатися у цій візії, якій не мало часу присвятив академік Леонід Рудницький.

[1] Proceedings of the Internаtional Scholarly Conference Marking the 120th Anniversary of Josyf Slipyj. The Ukrainian Quarterly: A Journal of Ukrainian And Interнаtional Affairs. Volume LXVII, Numbers 1 – 4, Spring-Winter 2011 [sic.]